The Swing Riots in 1830 -1832 represented the largest rural uprising since the Peasants Revolt of the 14th century.

The riots were born out of the desperate situation of the poor agricultural labourers. Their wages were dependent on the harvest, and they relied on the winter work of threshing the corn by hand to keep their families from starving. The introduction of the threshing machine in 1830 meant that this winter work was no longer available, or at the very least, wages were much reduced. The situation was desperate, and rioting broke out in Kent, initially in Lower Hardres, just 6 miles from the village of Barham, spreading quickly to neighbouring areas.

The first indication of trouble would be a letter from ‘Captain Swing’, which would be sent to local landowners and dignitaries, demanding higher wages and the destruction of the threshing machines. If there was no response, groups of 200 or more farm workers would gather, burning barns and breaking the hated threshing machines. Despite the large scale destruction of property, no-one is believed to have been killed during these riots.

As might be expected, many rioters were harshly dealt with; 2000 people were arrested, over 500 were transported and 19 were executed, including a 12 year old boy. However, Kent rioters were more fortunate, as they were tried and sentenced by local justices who were sympathetic to their plight. Four were executed, 48 were imprisoned and another 52 transported to Tasmania or New South Wales.

The 30th October edition of the Kentish Gazetteer records that a Mr Sankey’s threshing machine at Digges Place in Barham was destroyed, with some of the rioters being transported for life.

William Dodd, a farmer of Upper Hardres, had 2 threshing machines smashed; George Youens subsequently confessed to the crime. The case was heard by Sir Edward Knatchbull at Canterbury in October 1830. He gave the perpetrators a lenient sentence of a caution and 3 days in prison.

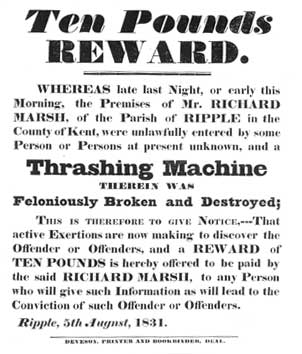

Robert Peel and his Tory Government pressed for more severe treatment of offenders. When, in August 1831 Richard Marsh of Ripple near Dover had his threshing machine broken, the culprits received a sentence of one year of hard labour.

This sets the context in which four Willis families in Barham decided in 1836 to leave the village, and England’s shores – and emigrate to the United States of America. As Joseph Willis – aged 9 at the time – described conditions looking back from old age: ‘Conditions were very hard to get a job in England at that time.’

Following on from the riots notices began appearing in local gazettes and newspapers advertising space on ships bound for the colonies. The following is an example, published in the Norwich Mercury on March 19 1836:

EMIGRANTS:

Positively to sail on the 10th April (having the whole of her cargo engaged). FOR NEW YORK. The fine, fast, well-known sailing ship CALISTA, John Ross Jameson, master, 500 tons burthen, lying in the London Docks. This vessel has superior cabins on deck and seven feet height between decks in which families can be accommodated, with separate berths, built under their direction either in the intermediate space or in steerage. For passengers apply to Oxley & Taylors, 8 George Yard, Lombard Street. Parish authorities sending out families will be liberally treated with. Bricklayers and carpenters are much wanted and to whom very high wages are given immediate employment on their landing.

Four children of Thomas Willis [1772-1837] and Ann Pierce [1772-1842] in Barham made the decision to up-sticks and go in search of a new life in the ‘New World’:

- Joseph Willis (1797-1868) & Elizabeth Hood and their 8 children;

- James Willis (1801-1877) & Elizabeth Prebble and their 3 children;

- Jarvis Gambrell & Mary Willis (1810-1874) and their 4 children;

- William Willis (1812-1899) and Mary Maythan

Shipping lists for two of these families have been located, and show the following:

- Joseph & Elizabeth Willis (nee Hood) were married in Lyminge in 1822. They sailed to New York on board the Calista and disembarked there with their seven children on Jun 2 1836.

- Jarvis and Mary Gambrell (nee Willis) were married in Folkestone in April 1840. They sailed from London on board the Westminster, setting foot in New York with their four children on Apr 6 1849.

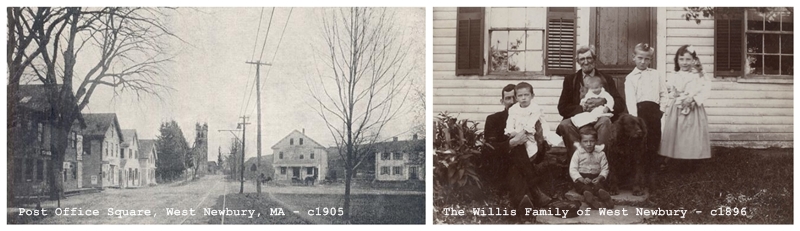

The families soon settled in West Newbury, a small town in Essex County, Massachusetts. Apparently, there were several families from Barham and the surrounding areas in West Newbury at the time. Kennett, Quested, Cooper, and Keeler are some of the family that have ties to Kent.

So what occupations did the emigrants take upon their arrival in the New World, having escaped the poverty of rural England?

Well, having spent two months at sea on a freight vessel Joseph and Elizabeth Willis and 8 children landed in Boston, Massachusetts before moving onto Andover, about 23 miles inland. That town was their home where they got work in the textile mills and on the farms.

According to the US and Massachusetts State Censuses, the families and their descendants worked as Shoe Makers and Comb Makers.

Joseph Robert Willis had a particularly colourful youth:

In 1840, when he was 12 years old he left home and shipped on a freighter as cabin boy. He was gone two years before returning home.

In 1845, aged 17 years old he went to New Bedford, MA (nearly 100 miles from West Newbury) and signed on a whaling vessel and was gone four years – and again returned home.

As Joseph’s grandson, Walter recalled in later life:

In them days, there was always work on the farm. Farm work was done by men and horses. The pay in them days was from 15 to 25 dollars per month with board. About all the hay and grain was cut with a scythe or cradle. That was before horse-drawn mowing machines came out.

Gramps worked on farms and cut cord wood and finished his working days in the comb shop until 1903 the comb shop closed.

The descendants of those first immigrants from Barham went on to better things – for example, Eugene ‘Shike’ Willis, who was Police Chief of West Newbury for almost a quarter of a century.

Sources: