The following article was written by Daphne Argent, and was published in the January 1999 issue of the magazine ‘Bygone Kent’. Read more about the village in ‘Whitfield within living memory (Part 2)’

The introduction to an article often recalls the early years of a century but as the date of my own birth in the 1930s recedes further and further into the past it would seem appropriate to remember how Whitfield, just outside Dover, appeared to someone who spent the 1940s and 1950s living there and to whom the village seems recently to have again changed its character with the building of the new bypass.

What of Whitfield since the 1940s?

The war years have their own memories; shrapnel everywhere just waiting for small children to collect and swap with friends or take to school, in the fields between Archers Court and Sandwich Road rival gangs of local boys played out their war games among the trenches dug across them to prevent enemy gliders from landing. The younger children were not evacuated from the village and during the most active part of the Second World War, school for these children was in the local village hall, and all age groups taught together by one teacher. If there was an air raid it was down under the tables until the danger had passed.

Normally, school was the Earl of Guilford’s Elementary Free School at Waldershare. This was a long low-lying building on the edge of Waldershare Park. The headmaster was Mr Howarth, a very fearsome man who lived in the school house with his wife, who taught the ‘tinies’. Their son Peter had been killed in the war and they also had a daughter called Mary. The school house was in the middle of the block with two classrooms at each end. Each of these was divided by a moveable partition that could be pulled back to make a larger room. The toilets were outside in the yard and a separate building housed the kitchen where school dinners were prepared. These were eaten off low tables covered with blue and white cloths; overcooked cabbage and lumpy custard spring readily to mind! Teachers remembered from those days were Mrs Harding, Miss Armstrong, Mrs Christian and Miss Appleton (known to many of the pupils as Crabby!). In her room there was a large copy of Gainsborough’s ‘Blue Boy’ hanging on the wall. The playground included access to the surrounding woods which were used for many games. There were tall, straight fir trees and beech trees with knobbly roots, all ideal for games of ‘off the ground’ or ‘tag’. In the spring the woods were covered with anemones and wild garlic, the latter giving off a strong pungent smell. Children came to Waldershare from many local villages and at the end of each day a coach from Hampshire’s of Eythorne collected them up and delivered them home again.

Whitfield had Special Constables and ARP wardens during the war and the village policeman at this time was Reg Mead. He lived in a house in Forge Alley leading from Sandwich Road to Lenacre Lane. The bus services 87 and 88 to Ramsgate and Elvington stopped at the top of this alley and next to this bus stop was the post office. It was really the front room of a house and was run by Mrs Bean who lived there. The postman was Bill Wickes who delivered the letters by bicycle. Next to the policeman’s house was a low cottage with a large garden, called ‘Tyneside’. This was occupied by Mr Morgan and his daughter Winnie. He would often stand by the gate in either a trilby or a panama hat passing the time of day with anyone who walked by.

The ‘forge’ no longer operated and was, by then, turned into cottages. Broadley’s farm, further up Lenacre Lane, provided milk for the village with both Maurice and Edward Broadley taking out their pony-drawn milk carts, with the churns on board, stopping at each house where the milk was ladled into jugs brought out by the occupants. These in turn were covered with beaded muslin cloths and put in the coolest part of the kitchen William ‘Bill’ Broadley owned much farmland around the village and the journey to St Peter’s Church was through his land. Whether it was across the public footpath or along Napchester Road the journey was accompanied by the sound of the skylarks that nested in the fields. Amongst the corn grew scarlet pimpernels which were studied closely by the children as a weather predictor! The walk across the fields during the war meant the counting of barrage balloons swaying on their invisible cords to protect the Dover coastline. They showed up best silhouetted against an evening sky. Of course they were subject to attack by rogue aircraft bust as fast as one was shot down it was replaced and the line was usually complete.

Providing food during the years of rationing was a time-consuming activity for a rural village with only two small shops. One of these was in Mill Alley and was a corrugated roofed chalet run by Mr Dewell, and later by Mr Moat. Looking back now it seems incredible that this little store with its bacon slicer, cheese wires and tins of broken biscuits was able to supply the local needs. Ration books were checked and coupons cut out or rubber stamped. Just occasionally there was something ‘extra’, but not often. People who had the space kept hens to provide them with eggs. Even then there was a limit to the number that could be used by each household and extra eggs were washed and graded and boxed in special egg crates for collection by Stonegate South Eastern Egg Farmers. This was a delicate task as breakages were to be avoided at all costs.

In the middle of the village was Guilford Nursery, a long-established market garden enterprise owned by the Williams family. This occupied all the land between Nursery Lane and Lenacre Lane stretching to the alley behind Cambridge House. To people now living in the bungalows and houses in this area this may come as a surprise as the only reminder of this old nursery is in the names of their roads. In addition ‘The Acre’ was also owned by the Williams family and every year was put down to potatoes. The harvesting of this crop was a back-breaking exercise each September.

Much of the produce was grown under glass and the greenhouses were heated by large iron pipes fed from a coke-fired boiler. Looking after this was a twenty-four hour a day commitment as it had to be ‘fed’ incessantly during most months of the year. It was down in the ‘cokehole’ and was an iron monster with a large door that opened to reveal a mass of red-hot coals. No matter what else was happening in the village or the world, the boiler routine had to be adhered to; 6 o’clock in the morning and at intervals during the day and again in the evening – no chance of a day off or a holiday The greenhouses grew lettuces and tomatoes in season and one house was devoted to arum lilies. These needed special conditions and had to peak for Easter Sunday when hundreds of blooms were needed for the local churches and for Canterbury Cathedral.

Much of the produce was grown under glass and the greenhouses were heated by large iron pipes fed from a coke-fired boiler. Looking after this was a twenty-four hour a day commitment as it had to be ‘fed’ incessantly during most months of the year. It was down in the ‘cokehole’ and was an iron monster with a large door that opened to reveal a mass of red-hot coals. No matter what else was happening in the village or the world, the boiler routine had to be adhered to; 6 o’clock in the morning and at intervals during the day and again in the evening – no chance of a day off or a holiday The greenhouses grew lettuces and tomatoes in season and one house was devoted to arum lilies. These needed special conditions and had to peak for Easter Sunday when hundreds of blooms were needed for the local churches and for Canterbury Cathedral.

The open land within the nursery was intended for flower cultivation but this was supplemented during the war years with the keeping of poultry and pigs. The latter had to be killed under licence during rationing but sometimes one mysteriously ‘vanished’ and the local people had a good supply of pork for a few weeks. The chickens were for the Christmas trade and provided birds for village families. These birds were killed and then hung by their legs, with their heads still feathered, awaiting cleaning and sale. Some people kept back enough birds to do this to supplement their own income and they became a familiar sight hanging in rows in garden sheds.

The nursery also grew Christmas trees and each autumn many were dug up, or cut down if someone wanted a large one. The tallest, oldest trees were to be found at the lower end of the nursery near Lenacre Avenue and the Acre and this was a dark, spooky place for children walking down the lane. Holly was also used a great deal in these years to make decorative wreaths, often 100 or 150 a season. It was also sold in bunches for decorating houses. Wreaths were made by grassing a wire frame and then pushing in individually wired pieces of holly. These had to be clipped and wired by the sackful. Berries were wired separately and pushed in after the leaves. The nursery would buy holly from trees around the village and then cut it down and use it. The wearing of a sacking apron and thick gloves was an essential part of this activity! The most attractive but most pain-producing variety of holly was one with tiny curled leaves, more prickles than leaf surface, called appropriately ‘hedgehog’ holly.

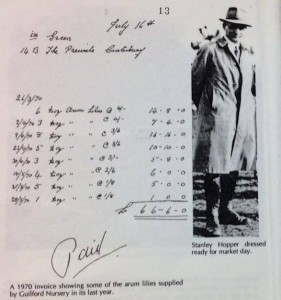

At other times of the year the wedding and funeral trade used many of the flowers grown there. There were many local brides whose bouquets were made by Stanley Hopper at Guildford Nursery. As children we were intrigued by the different kinds of frames that could be used for the funeral tributes. There were cushions, a harp with a broken string, crosses, and gates of heaven. The resulting flowered offerings were an art form and involved hours of mossing, greening and flower wiring. Old invoices show that the prices paid for such work often did not reflect the hours of care that had been put into them. Other invoices show another part of the nursery trade, providing ‘bedding’ plants for gardens, long before the days of garden centres. Seeds were sown and then the small plants were pricked out each spring and were nurtured in greenhouses and frames until they were ready for sale.

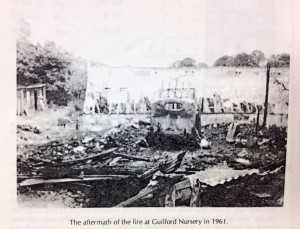

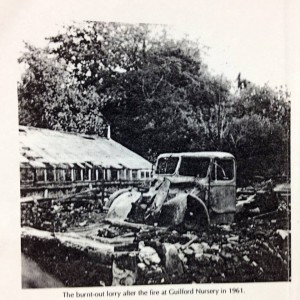

Many of these plants were taken to Dover market each Saturday, for the nursery had a produce stall outside Lloyds Bank in Dover’s Market Square. This was manned each week for fifty years by Stanley Hopper who was first employed by the Williams family and later ran the Nursery in his own right, eventually retiring in 1970. As well as plants the stall was an outlet for their many varieties of cut flowers, especially dahlias, tomatoes and other salad crops. Each Friday the Bedford lorry was loaded with trestles, tubs and boxes ready for an early start on Saturday mornings. Some weeks the lorry would be full to overflowing, and the physical and economic damage caused one week in 1961 when fire broke out in the ‘lodge’ where the loaded lorry was garaged can be imagined. Lorry and contents were all destroyed the loss of more that one week’s income.

Over the years parts of the nursery land were sold for residential development and now only the original house, once occupied by John Williams and his family, still remains to mark the place where all this activity took place.

Daphne was born 13 March 1934 in the village of Whitfield, just outside Dover in Kent and died on 24 January 2014 in Rochester, Kent, just weeks before her 80th birthday. She was the daughter of Stan Hopper and Dorothy White.

Daphne was born 13 March 1934 in the village of Whitfield, just outside Dover in Kent and died on 24 January 2014 in Rochester, Kent, just weeks before her 80th birthday. She was the daughter of Stan Hopper and Dorothy White.

Daphne spent years researching the history of her ancestry and was fastidious in her methods. In the decades before the internet she spent many hours in local libraries trawling through parish records and census returns, traipsing through church yards and cemeteries locating family gravestones and – unbelievable in today’s technological age – painstakingly wrote out family trees by hand (and frequently re-wrote them when corrections and updates were required). She built up connections with a world-wide network of fellow genealogists also keen to discover their Hopper roots. The quantity and quality of her work is valued greatly by many. Indeed, a large proportion of the data on the Willis Tree relating to my mother’s line comes from Daphne’s endeavours.

She is greatly missed -this article is presented here in her memory.

[Special mention to Mark Jennings of the ‘Whitfield, Dover, Kent’ Facebook group who originally posted the article and accompanying photographs]