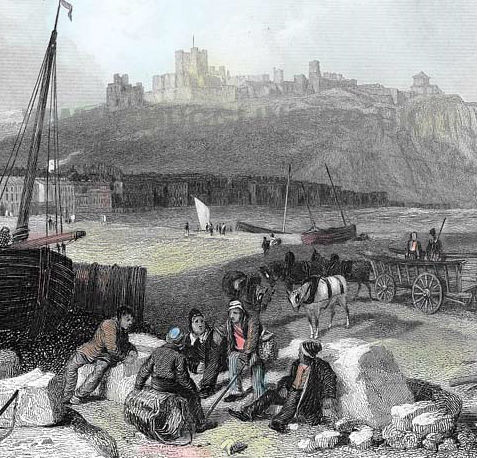

The white cliffs soaring high above Dover form a landmark that is visible on all but the darkest of nights. Smuggling was rife in Dover, and by 1745 there were reported to be 400 men involved in the business, with no other obvious source of income.

There had been a Customs House in the town since the thirteenth century, and by 1822 a total of sixty two men were employed in the customs service. Indeed, one would have thought that smugglers returning to Britain would have taken pains to avoid the town itself, since Dover was a local centre for the preventive forces, and soldiers from the castle were always on hand to strengthen the arm of the customs officers or blockademen.

In the early nineteenth century, the men of Dover, Folkestone and Hastings built up a trade in golden guineas (coins worth £1.05), which could be sold in Paris for thirty shillings (£1.50) apiece and were then used to pay Napoleon’s armies. Galleys carrying the guineas across returned with silk kerchiefs, French lace, gloves and other luxuries. It is said that one galley, facing a strong northerly breeze, was given a tow out to sea by the Dover steam packet. Despite the wind, the strong rowers aboard the galley were able to reach the French coast ten minutes before the steamship.

English smugglers were useful to Napoleon in other ways too. They carried newspapers and reports from French spies based in England, and even took the spies themselves back and forth across the Channel, keeping them hidden in safehouses and helping them to disperse about the country.

Tea had become the English national drink by the end of the seventeenth century. Smuggled tea was brought into the country in parcels wrapped in waterproof oilskins, known as ‘dollops’. It is said that at the height of the smuggling era, over two-thirds of all the tea drunk in Britain was supplied by smugglers.

Before the mid eighteenth century most of the smuggled tea was brought to the south coast aboard Folkestone cutters of between forty and fifty tons. These vessels would be met two or three miles off the shore by smaller boats, and would carry between twenty and thirty cargoes to England in a week. Folkestone smugglers had such close ties with Flushing that local shipbuilders started businesses there.

Large numbers of men were involved in smuggling at Folkestone, supported by many members of the local community. Local customs authorities here were quite clear about the allegiances of the Folkestone people. One commented: As most of the inhabitants of Folkestone, Sandgate and Hythe are in the confidence of the smugglers, no information can be expected of them.’

When a Folkestone ship was captured and her crew thrown into Dover gaol in 1822, a group of relatives and friends gathered and began to march to Dover. At the gaol, the military commander decided not to open fire on the crowd, which then proceeded to climb onto the building, causing so much damage that the crew was able to escape.

1826: The Aldington Gang

Perhaps because of the deterrent effect of so many representatives of the forces of law and order, accounts of smuggling in Dover itself are few and far between. However, the Aldington gang are known to have used the beach here, and what started as a routine landing of contraband for the gang in 1826 ended in disaster. Two blockade men were on patrol among the bathing machines which then lined the beach when they spotted the attempted landing. One of the pair, Richard Morgan, was a brave officer who had killed a smuggler the previous December (you can still see the man’s grave at Dymchurch). Morgan fired a shot to summon help, and the smugglers returned fire, killing Morgan and injuring his colleague.

With the killers still at large, the dead blockademan was buried in St Martin’s churchyard, but the incident sparked off a concerted attempt to round up the gang and bring them to justice. A £500 reward was offered for the arrest of George Ransley and the rest of the gang he led. One smuggler turned King’s evidence, and the whole group were eventually rounded up and tried for a variety of offences: Richard Wire was charged with pulling the trigger. Though convicted, they narrowly escaped the gallows and were transported to Tasmania the following year.

Morgan’s killers didn’t hesitate to use violence when their livelihood was threatened, and armed clashes were becoming increasingly common at the time of his death. However, this doesn’t seem to have isolated the smugglers from the local community, since the reward failed to elicit any information about the crime. The impression of solidarity is reinforced by another incident just six years before when the population had turned out in force to free a group of smugglers imprisoned in the town gaol. A revenue officer called Billy ‘Hellfire’ Lilburn had caught eleven Folkestone and Sandgate smugglers on a run, and had them locked up in Dover gaol. Word soon got around, and the prisoners’ fellows raised a huge mob which quickly broke down the door of the gaol. When it was discovered that the captured smugglers had been moved to the most secure cells, the mob started to literally pull the prison apart, pelting the troops that had by now been called in with a hail of stones and tiles. The mayor of Dover arrived, but when he attempted to read the riot act, he was set upon, and gave up. By this time, Hellfire Lilburn himself had appeared, and tried unsuccessfully to persuade the commanding officer (reputedly ‘Flogging Joe’ McCullock, the founder and mentor of the Blockade) to fire on the crowd.

Eventually the smugglers were released, and made good their escape in hired horse-drawn carriages, the fore-runners of today’s taxis! They stopped at the Red Cow to have the conspicuous and unwieldy chains removed from their hands; meanwhile outside the mob continued to rampage through the town, smashing windows.

The gaol was damaged beyond repair and a new one had to be constructed. The whole event was commemorated in a folk-song:

“We smuggling boys are merry boys

Sometimes here and sometimes there

No rent nor taxes do we pay,

But a man of war is all our fear.

‘Twas on the 21 st of May,

As you will understand,

We sailed out of Boulogne Bay,

Bound for the English land.

But to our sad misfortune,

And to our great surprise,

We were chased by two galleys,

Belonging to the excise.

Oh then my boys for liberty,

Was the cry of one and all,

But soon they overpowered us,

With powder and with ball.

They dragged us up to Dover Gaol,

In irons bound like thieves,

All for to serve great George our King,

and force us to the seas.

The wives for their husbands

Were in such sad distress,

For children round the gaol

Were crying fatherless.

And sure the sight was shocking

For any one to see,

But still the cry came from the mob,

For death or liberty.

Oh then a hole all in the wall,

Was everybody’s cry.

And Lillburn and McCullock’s men

were soon obliged to fly.

For bricks and tiles flew so fast,

From every point you see,

And these poor men from Dover gaol,

They gained their liberty.

And now they’ve gained their liberty

The long wide world to range,

Long life to the Dover women,

Likewise to the Folkestone men.”

NOTE: No individuals currently listed in The Willis Tree are known to have been involved in smuggling, but if links are subsequently found I will update the site accordingly!

You can read all about smuggling in East Kent at www.smuggling.co.uk/gazetteer_se_14.html