3. John Fagg discusses the bleak future of the Harbour

‘The day was dull and Mr John Fagg’s private room at the warehouse overlooking Paradise Pent was gloomy, but not a whit more gloomy than the faces of the four gentlemen present there. It was, however, speedily shown that the news which Captain Maxton had a few minutes before brought from Boulogne was not the cause of the dismay.

“So they’ve guillotined the French King, have they?” muttered Mr Crundall.

“Chopped his ‘ead off, eh?” Captain Pepper grunted, after emptying his glass of moonshine brandy.

“That’s what they’ve done, Valentine,” nodded the skipper of the Emma. “An’ what’s more I’m damned if they don’t sound delighted with what they’ve been a doing.”

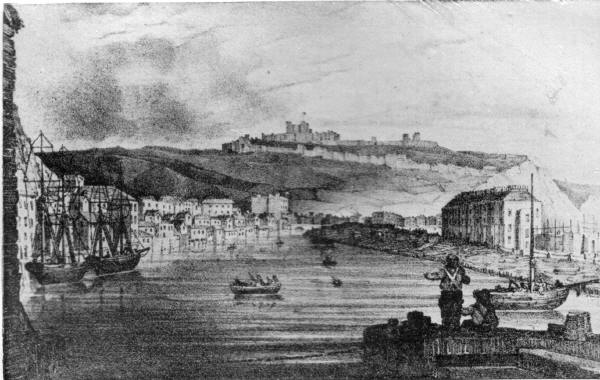

There was a little idle talk on the topic between the three of them, with John Fagg still standing at the window, glancing unseeingly towards Paradise Pent and the spot where Limekiln Street filtered out at the margin of the desolate waste.

He turned at last and spoke to the boatbuilder.

“Well, Kit”, he remarked dourly, “it seems very much as if we’ve been wasting a lot of time.”

Mr Crundall swore violently. “Aye,” he agreed. “An damn me if I hadn’t looked forrard like a child to putting a 700-ton ship into the water.”

“What’s been done before can be done again,” roared Captain Pepper.

“The Harbour Commissioners’ll do no more after this,” snorted Captain Maxton. “Now they’ll take up their old attitude, and that means they’ll continue to regard the bar as being as much inborn as sin.”

“Any point, John,” asked Mr Crundall, “in having a word with Sir Walter Plumbley?”

John Fagg laughed shortly. “What do you think, Kit?”

The shipowner began to pace restlessly, his mind active, his jaw pugnacious. It was, however, a chance remark of Mr Crundall which brought his thoughts to quick life. That worthy philosophically observed that he was sorry both for himself and for John Fagg.

“Thankee, Kit, for your kind words of consolation,” said John Fagg, smiling queerly. “And the same to you, too, though I can plainly see that you ain’t particularly concerned about what’s happened.”

The boat-builder’s eyes nearly popped out of his head. “Not concerned!” he growled. “You leave me to speak for myself.”

Within a few moments Mr Crundall was near to rage as John Fagg tantalisingly outlined the impotence of the traders of Dover. It would appear, Mr Fagg concluded blandly, that the townsfolk of Dover must suffer their ills with as good a spirit as they might, for having no control over the thing which brought in their livelihoods, there was nothing else that could be done.

“We can raise hell with the Harbour Commissioners, can’t we?” snapped the boat-builder. “For that’s my humour.”

“Mmmm,” murmured John Fagg. “But there’s a surer fashion of bringing the Commissioners to heel.”

“What do you mean, John?” Christopher Crundall growled.

“Listen,” said the shipowner.

He spoke of the Harbour Commissioners and of the policy adopted for generations. The revenue of the Commissioners, he said, was derived from three sources. The first resulted from a half-share in the Passing Tolls and was like to be taken away altogether unless the harbour was considerably improved; the second came from the harbour dues, a rapidly shrinking source; and the third was provided by receipts for ground rents.

“But where has their ground come from?” he demanded. “From shingle thrown up by the sea, which they have seldom attempted to move as was their bounden duty. They preferred to let it stay, allowed its consolidation into firm land, subsequently deriving the major part of their income from its use for building purposes.”

“Surely so,” pondered Mr Crundall, on whom a vague light was beginning to break.

John Fagg, keyed up by his deep disappointment, drove home point after point to demonstrate his belief as to how the Commissioners, indirectly, should be dealt with. It was, of course, not possible, he explained, to mulct the Commissioners of the valuable ground rents they already enjoyed, but it might be possible to prevent them from adding further to this same source.

“The Commissioners may be lessors of reclaimed ground,” he said significantly, “but if there are no lessees coming forward, then where are they? In such cases the Commissioners must perforce seek extra income from the other two sources, and that means they must inevitably find the money for the substantial improvement of the harbour, not merely for its grudging repair, as they do today.”

“And how would we stop folk from building on reclaimed land?” asked Mr Crundall.

“Who leases it?” countered John Fagg.

His audience scratched their heads awhile. Finally it came to them that the folk who were thus defeating Dover’s own interests were the people of the town itself.

“That’s why we must educate ’em,” said Mr Fagg grimly. “We’ve got to make ’em see that sooner or later it means ruin to ’em. Ram it down their gizzards until they see the light.”

Mr Crundall, if shrewd, was a slow-thinking man. It was only when it dawned on him that all the houses in the vicinity of Strond Street, and all the big district between Round Tower Street and Beach Street, had been built on the site of Dover’s former haven, Paradise, that he saw the full force of the argument which he had heard.

“Why…” he jerked his head towards Paradise Pent, “good ships have floated in all them places,” he said aghast.

“Aye,” growled John Fagg, “and the Tidal Harbour, the Basin and the Pent’ll all go the same way if we don’t watch it.”

“We’ll watch it, then,” grunted Mr Crundall, turning up the collar of his heavy coat…